This morning at the Oval, Josh Hull will become the 716th England cricketer to play in a Test. Hull’s first cap, at the age of 20, will encapsulate a summer of regeneration – a season in which the talent pool in English cricket, both at Test level and below, has been replenished.

Hull will join a Test side expecting to win every home game of a season for the first time since 2004. While that imminent feat cannot disguise the fact that the English summer has rarely been captivating, the campaign has seen a new generation of talent flourish.

The phenomenon is particularly evident in the Test team. The first iteration of Bazball was largely shaped by the exceptional performances of established players, newly liberated and emboldened. Jonny Bairstow’s extraordinary batting in 2022 was the catalyst for the new approach; James Anderson and Stuart Broad were both recalled, to great effect; Chris Woakes and Mark Wood helped transform the 2023 Ashes.

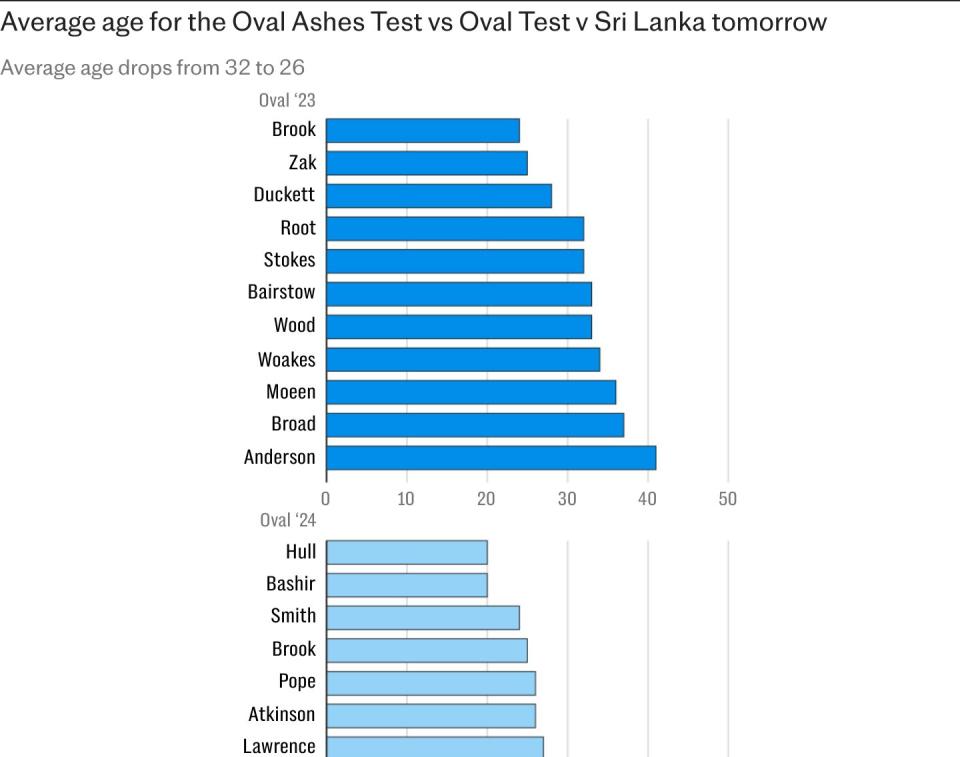

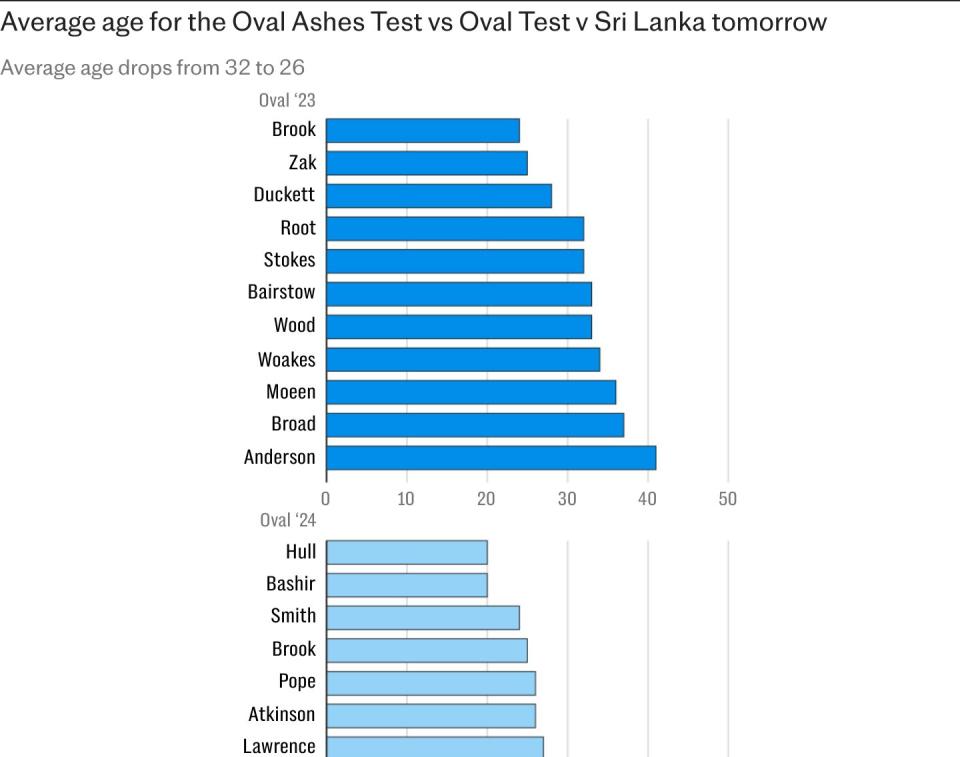

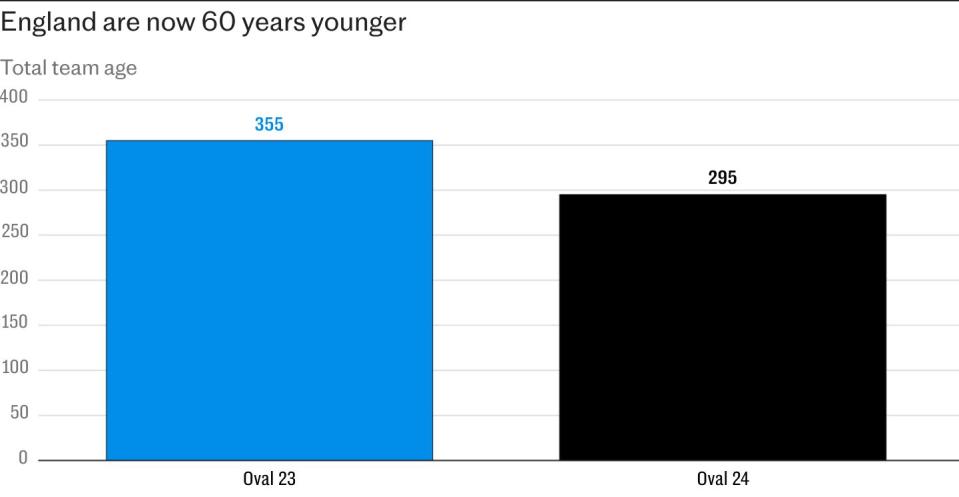

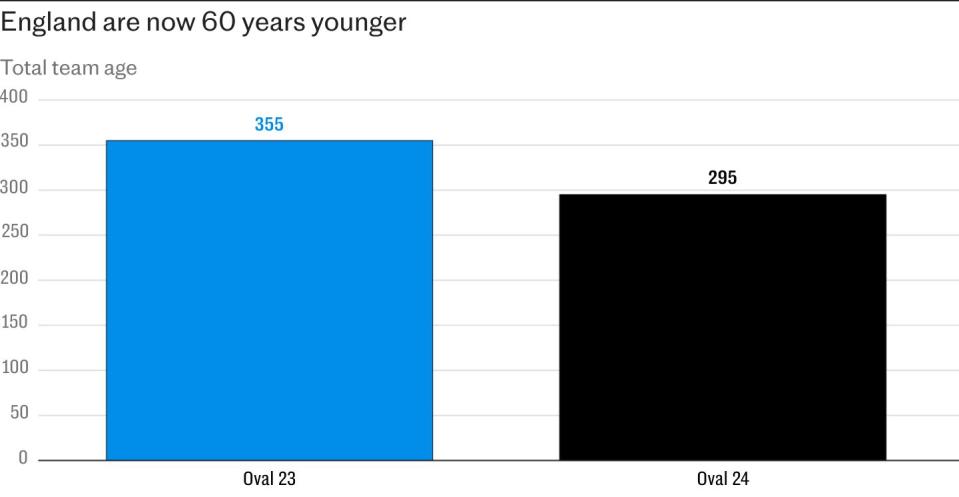

A new generation has emerged. Last year at the Oval, the average age of the English team was 32; with only four survivors of that XI, the average age for this week’s Test has fallen to 26.

In less than two months, uncapped players have become senior players, as if by osmosis. Gus Atkinson and Jamie Smith, who both made their Test debuts on July 10 at Lord’s, have shown a combination of skills well-suited to the international game and even-tempered temperaments that have made them both comfortable in the team.

Hull’s choice fits in with the guiding principle of England’s regeneration: focus on a player’s qualities, not his domestic results. Hull has taken just 16 wickets at an average of 62.8 in 10 first-class matches. Yet Brendon McCullum has identified the Leicestershire bowler as a “diamond in the rough”, due to his 6ft 1in height and the angle of his left arm.

It was this reasoning that led to Shoaib Bashir being selected to tour India earlier this year with a record average of 67. Bashir, though still developing his right-handed talent – he will enjoy the roughness created by Hull’s footprints – produced a solid performance after supplanting Jack Leach as first choice spinner. Leach remains Somerset’s first choice, but for England such considerations are moot: they consider the attributes required to succeed in county and Test cricket to be completely different.

The same logic will now apply to the white-ball team, especially after McCullum was appointed as all-format coach. A poor performance in the T20 World Cup in June ended Matthew Mott’s tenure, after a run of three wins in 12 matches against Test opponents in the last two World Cups.

While the spirit of regeneration extends to limited-overs cricket too, England’s T20 squad for the series against Australia, which begins on Wednesday, includes six players not selected in that format. Jacob Bethell, 20, a Warwickshire left-hander with a big back and a huge amount of self-belief, is perhaps the most effervescent.

For all the attention on the England team, the sense of regeneration extends to county cricket. This is particularly evident in the children from the 2005 Ashes team who have made their way into the counties: Rocky Flintoff, 16, at Lancashire and Archie Vaughan, 18, at Somerset.

Other teenagers are also in fine form. Farhan Ahmed, Rehan’s 16-year-old brother, took 10 wickets on his County Championship debut for Nottinghamshire against Surrey last week. In the same match, Fred McCann, 19, took 154 wickets from number three. Ben McKinney, the 19-year-old Durham opener, has an attacking game tailor-made for England’s needs; much is also expected of Warwickshire’s 18-year-old middle-order batsman Hamza Shaikh. Harry Moore, 17, of Derbyshire, could one day be Ben Stokes’ successor as a bowling all-rounder.

The new wave of young county cricketers is not just about their own talent. They are also benefiting from wider changes in English cricket.

The first is the Metro Bank One-Day Cup. Although the competition has been marginalised, with top players featuring instead in the Hundred, it has had an unexpected benefit. “From a player development perspective, the One-Day Cup has provided opportunities,” says David Court, England’s head of player identification and talent pathway. The young players’ strong performances in the One-Day Cup have also earned them selection in the County Championship.

The second change is a better alignment of England teams below the senior team. England use the Lions, their second team, as a way to accelerate the development of players of potential, regardless of their results at home. The England Lions team that crushed Sri Lanka last month included Ahmed and Shaikh, both making their first-class debuts. “That progression from Young Lions to Lions to the senior team is closer than ever,” Court said. “We are identifying players with a similar mindset and approach to what we need in the national team.”

The third change is the ability of the England national team to lead by example. “England have opted for younger, more optimistic players,” says Court. “So young players have the opportunity to progress quickly through the system, without necessarily having spent years in county cricket.”

England’s promotion of youth in international cricket has highlighted the counties’ historical conservatism, also encouraging them to embrace teenage kicking. With England having already made Rehan Ahmed their youngest ever Test player and seen him take seven wickets on debut, Notts making his younger brother Farhan their youngest County Championship cricketer seemed downright risky.

As he begins his new role as top coach, the regeneration of talent has convinced McCullum that England should challenge India for world cricket dominance across all formats.

“There’s a lot of great talent in English cricket and it’s about showcasing it and bringing it together,” McCullum said ahead of the final Test against Sri Lanka. “With the passion for the game in this country, with the history and tradition of the game, the fact that it’s incredibly well supported, the structure and the talent pool that’s in this country, there’s no reason why they can’t challenge India in that regard for all the major titles. There’s no reason why they can’t.”

So a summer in which cricket struggled to attract attention may well have a lasting legacy. The 2024 season could be seen as a year of profound regeneration – and the moment when English cricket, once and for all, learned to shed its distrust of youth.